Memories of Village Life

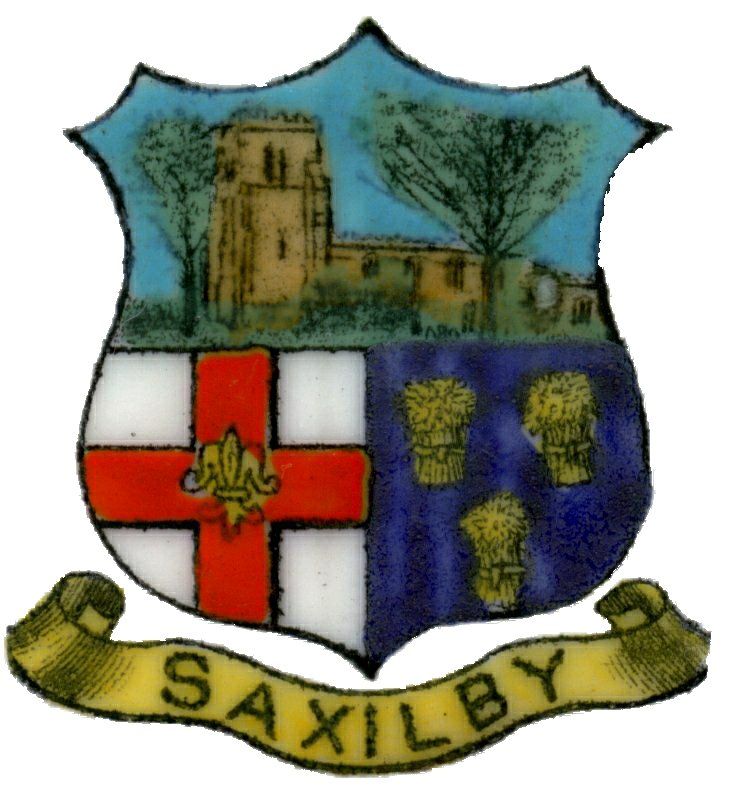

‘The History of Saxilby and the Cavill Family’ by Sheila Woolner (nee Cavill) [1927 – 2011]

Sheila wrote these wonderful village memories for us when the Group was formed in 2000.

‘There are still one or two Cavills in Saxilby today, and I like to think our name will carry on for a very long time.

Even though I am no longer a Cavill, I still feel I belong to the village – although when I look back on how Saxilby was when I was a child, I feel a little sad. The population was about 1,200 then and we all knew each other.

There were fourteen shops and two policemen, who could be seen every day ‘on the beat’.

Hutson’s bus ran every hour to Lincoln and would stop at anyone's gate to pick up and drop off.

We could go for walks up Mill Lane as there were hardly any houses up there then; just fields and Lawson’s Gardens. We could skip and play whip and top in the street with hardly any traffic to interrupt us.

I suppose we have to make way for progress, but I’m afraid I liked it better the way it was.

Historical records, which used to be in Saxilby Church and have now been moved to Lincoln Cathedral, show that there was a Cavill family in the village when Elizabeth I was on the throne. [The Churchwarden’s Accounts are now held in the County Archives].

The earliest story I have heard about the family was in the early 1800s. The village, which consisted of a few places by the canal, was badly flooded. The women and children had to be taken by Ned Cavill [1783-1859] in his donkey and cart to take refuge in the church until the flood subsided. This story was told to me by my father, as he found an old book when he was clearing out Miss Kirkby’s shop on the waterfront. Unfortunately, the owner of the property took the book and we lost track of it.

[Fortunately, the Group has a copy of the flood report made at the time. “Mr Edward Cavill of Saxelby is 75 years of age: remembers the Spalford Bank breaking, and the flood, Candalmas 1795. The water came into his father’s house and shop in Saxelby, and into the ‘Sun’ public-house, as high as the top of the lower sash of the window. Barrels were placed on their ends, and planks laid from one to the other in the house to walk upon. Several of the inhabitants removed to the higher part of the town, and many of them had to live in the church. The water remained about three weeks.”].

My great-grandfather, Thomas Cavill, and his large family lived by the canal behind Foss Dyke House, Gainsborough Road, in a small cottage on the bank side. He worked in the brewery, which I think has been turned into living accommodation now. His gravestone can be seen in the old part of the graveyard. [Thomas Cavill, Foreman Maltster, 1822–1894].

My grandparents were a very refined old couple [Alfred 1864-1937, Hannah 1864-1937]. The eldest of their children was born in 1887 when my grandfather was a porter for the Great Northern and Great Eastern Railway [GNGER]. They went on to have nine more children and then my father [Alfred] came along in 1899. Sadly three of their daughters died in one week from whooping cough in a terrible epidemic in the village [1890]. My grandfather was now a platelayer for GNGER. They had fifteen children in all and lived in a railway cottage on Sykes Lane.

My grandfather left the railway before the First World War and had to move house. As far as I know, they lived in the farmhouse which is now the riding stables [now Stable Yard, opposite the junction of Highfield Road and the High Street].

Three of their sons fought in the First World War. Happily, they all came back but my father was gassed in the trenches and was never quite the same again; there wasn’t any counselling in those days.

After a few years, my grandparents then moved to the house next to Foreman’s Car Sales. My grandmother used to serve teas in the front room. I remember seeing one of those metal adverts which said ‘Teas with Hovis’, which was fastened on the front garden wall.

My grandmother died in April and my grandfather in November of the same year [1937] and they are both buried in Saxilby churchyard.

Most of their family left the village as the girls all went into domestic service. However, the sons all spent most of their lives in Saxilby. My Uncle Walter could have told us many tales about the village but sadly he died last year

[1999] at the age of 94. He was the youngest and last of the family.

When I was three Mr Sergeant gave my dad a job on the farm by the canal at Odder; its nickname was Misery Farm. My mum learned to push the flat boat over the canal to catch Charlie Hutson’s bus to school. The bus cost 6d [2.5p] a week for the return journey.

One of the highlights of the week was when Jubb’s van called on the other side of the canal. He would pip his hooter and mum would push the boat over and we would stock up on candles and paraffin or sometimes even a lamp glass or a stable lantern. We always had a few sweets; you could buy almost anything from ‘Jubbys’.

After 11 years we moved away from the village for a short while, but the call of Saxilby was too much for my father so we came back to live in the row next to the old farm cottages in the High Street. We think that those two cottages may have been stables for the Old Hall. There was a large beam in the kitchen along the wall which had rings in it, where the horses were probably tethered. There was a small cottage at the end which was probably the waggoner’s house.

There wasn’t any electricity until the end of the Second World War. The water was from a pump at the end of the yard. The toilet was an earth closet at the top of the garden. It was so far away from the house that my brother would go on his bike to it!

We started at the infant school when we were five. We called it the ‘bottom school’ and we went there until we were seven. Miss Smith and Miss Graves were the teachers. I Remember a pink curtain drawn across to divide the classes. There was a large elm tree in the playground we used to sit under for our lessons in the summer. The sun seemed to shine more then!

When we were seven we moved to the school at the top of the village which is now a nursery school. Mr Bartlett was the headmaster. He would ring a bell twice to let us know it was school time and woe betide us if we were late!

I attended school there until I was fourteen, as the Second World War had started. I left on my birthday and went to work in a factory in Lincoln.

Childhood Memories

The memories I have of my childhood at both Saxilby schools were quite happy and, although I think we were poor by today’s standards (my father was paid 30 shillings (£1.50) a week), we never felt it. We always had a present at Christmas and I had a new dress for the Sunday School Anniversary.

Most of us went to chapel or church every Sunday, two or three times a day. When the Godfrey Memorial Chapel was opened, I took the afternoon off school and went to the ceremony with a friend. We were in dreadful trouble at school the next day!’

There wasn’t much traffic to hinder us in those days. There would be a Co-op bread cart with a nasty horse that might bite, and Spencer’s milk float driven by Tom Ford. The meat was delivered by a lad on a trade bicycle. I remember Charlie Rogers the baker who had a bake house behind Miss Kirkby’s shop. He made lovely bread, which he baked in the early mornings and delivered in the day on his bike. There was also Sergeant’s coal lorry, as everyone had coal fires then.

Every autumn, we had two weeks holiday for potato picking; I always went to one of the farms. I can’t remember how much we were paid; although it was hard work, we had some fun!

The War Years

When the Second World War started, the village changed a great deal. We received evacuees from Leeds so that they could be sheltered from the bombing which was targeted at large cities. They were billeted with different people in the village although we didn’t actually look after any as our house wasn’t big enough. I am afraid the lads of the village didn’t think much of these ‘townies’ and, poor kids, there were several skirmishes in the village (but not if Mr Bartlett [the headmaster] knew!).

There was a searchlight battery stationed on Sturton Road and a Land Army hostel was opened nearby. Later the Land Army girls were moved to Ingleby Grange and stayed there until the end of the war.

At the time when invasion was threatened, a battery of Royal Engineers was stationed in Saxilby, using the old Wesleyan Chapel, the Village Hall, and some houses in the village. They erected a large marquee on the field which is now the end of Highfield Road. They asked for volunteers to work there, helping with simple munitions. I used to go after work; lots of young people went. We tied matches on strong rubber bands to make petrol bombs.

Saxilby was really busy at that time. We had two dances in the Village Hall every week on Wednesday and Saturday evenings. The lads who were billeted there early in the war would stack their beds up and the dance was held in the centre of the hall. Everything had to packed away by 11.45 pm as the place had to close by midnight.

After the war accommodation was very scarce in the village and several people moved to Fiskerton airfield, where the council had adapted some RAF huts into living places. Six new council houses were built on Queensway in Saxilby.

By this time, I had met Jack Woolner who was stationed at Wigsley. Jack and I were married in 1948 and lived with my parents for nine years.

After he had left the army, he worked on the LMS Railway for a time and then for the Danish Bacon Company, whose warehouse was down Sykes Lane in the old West’s Works offices. They had a smoke room for their bacon in the old Parman’s Garage which was at the foot of the old Saxilby swing bridge, which was disused once the new bridge over the canal and railway was built in 1937.

When I look back on how Saxilby was when I was a child, I feel a little sad. I suppose we have to make way for progress, but I liked it the way it was!'