The Tale of Tom Otter - Fact or Folklore?

The tale of a man who murdered his pregnant wife on their wedding night on 3rd November 1805 still endures. The story has been faithfully reproduced over the years. You can find the same version widely on the internet, and ghost-hunters regularly visit the Sun Inn at Saxilby, where the inquest was held. But how much of the story is folktale?

The Facts

Thomas Otter, christened at Treswell on 3 March 1782, was the son of Thomas and Ann (nee Temporal). He married Martha Rawlinson in Eakring, Nottinghamshire sometime during 1804; their daughter Mary was christened on 23 December 1804 in Hockerton, six miles north of Southwell.

During 1805, Otter was working in Lincoln, but under an alias by using his mother’s maiden name of Temporal. Contemporary newspaper articles describe Tom as ‘a stout, handsome man, about five feet nine inches high’, and describe his occupation as ‘a labouring banker upon one of the canals in the neighbourhood of Lincoln’. John S Piercy, in his 'History of Retford’, written in 1828, describes Otter as 'malicious and revengeful and cruel to horses and other animals. A remarkable instance of which is related of him. He cut the eyes of a living ass, he made an incision with his knife in the rump, on each side of the tail, and stuck them in!'

Newspaper reports continue ‘he became criminally intimate with a young woman, and she proving pregnant, he was compelled by the parish officers to marry her’. No one involved was aware that he was already married.

The Bastardy Act of 1733 stipulated that the supposed father was responsible for the maintenance of his illegitimate child. If he failed to support the child, the mother could have him arrested on a justice's warrant and put in prison until he agreed to do so. Parishes were obliged to maintain the mother and her child until the father could do so. Those parishes were to be reimbursed by the alleged father, though this rarely happened. In an attempt to stem the rising costs of poor relief, the local authorities attempted to reduce their liability for illegitimate children by forcing the fathers to marry the mothers. This was known colloquially as a 'knob-stick wedding', the fore-runner of a 'shot-gun wedding'.

South Hykeham Parish Register records the marriage of Thomas Temple (sic) of the Parish of St Mary Wigford in the City of Lincoln to Mary Kirkham of the Parish of North Hykeham on Sunday 3rd November 1805. They were married by the curate, Thomas Brown, in the presence of William and John Shuttleworth, Overseers of the Poor for the Parish of North Hykeham. Mary was about eight months pregnant.

It is far from clear what happened following the wedding, but for some reason Tom and Mary found their way to Drinsey Nook, an area on the Nottinghamshire/Saxilby border along the A57. They were seen by several people crossing Saxilby Bridge. The Staffordshire Advertiser reported the following week that 'the body of a woman was found the following morning; her head being beaten to a pulp, and a large hedge stake, with two bundles of cloaths

(sic) lying near her'.

Tom Otter was arrested by 'Patchy' White, a Lincoln Constable later in the day at the Packhorse Inn, in Lincoln High Street. He was escorted the following day to Saxilby for the inquest on Mary.

Although the contemporary reports do not give the location of the inquest, it is likely to have been held at the Sun Inn, the usual location for all parish inquests. Held in front of the Coroner, Mr Drury, and a jury of twenty locals, and with the body present (no photographers in those days!), a verdict was returned of Wilful Murder against Thomas Temporal alias Otter, and he was committed to Lincoln Castle.

Immediately following the inquest, Mary was buried in the churchyard of St. Botolphs, Saxilby, by Thomas Rees, Vicar of Saxilby.

The murder trial was held before Sir Robert Graham at Lincoln Lent Assizes on Wednesday 12 March 1806. There are few details of the trial, as most assize records for the Midlands circuit before 1818, including Lincolnshire, have not survived. The newspaper reports of the time give only a brief summary. Otter was charged under the name of Thomas Temporal. The trial lasted five hours. Twenty witnesses appeared, and although the evidence was circumstantial, Otter was found guilty, sentenced to be executed on Friday 14th March, and his body dissected. For some reason following the verdict, the sentence was changed from dissection to gibbeting.

The Murder Act 1751 includes the provision 'for better preventing the horrid crime of murder . . that some further terror and peculiar mark of infamy be added to the punishment'. The Act adds 'in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried', by mandating either public dissection or hanging in chains of the cadaver. The Act also stipulates that a person found guilty of murder should be executed two days after being sentenced. The Act was repealed in 1871.

The ‘Lincoln, Rutland and Stamford Mercury’ reported on 21 March 1806 – ‘

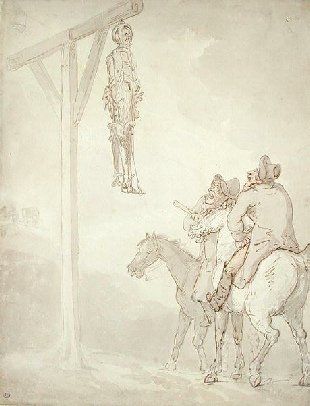

Thomas Temporell, otherwise Thomas Otter, was executed at Lincoln on Friday last, for the murder of Mary Kirkham. He acknowledged his guilt to the clergyman who attended, and to the keeper of the prison. His sentence was that his body should be dissected, but this day, at ten in the forenoon, it was taken from the Castle, and hung in chains on Saxilby Moor, near to the place where he committed the horrid murder. . . . Great numbers of people went this day to see the body hung to the gibbet post. He was measured for the chains a few hours before his execution: All his fortitude appeared then to forsake him, for the first time, and when taken to the gallows, he did not so much as hold up his head .'

Five years later, it was reported ‘

in the mouth of Thos. Otter, hanged in chains for the murder of his wife . . . there is a nest containing several young birds half fledged ’. The ‘Magazine of Natural History’ carried a similar report in 1832. ‘

It appears that, whilst the carnivorous tomtit was feeding on the flesh of the malefactor, he had an eye to a comfortable habitation in the vicinity of so much good cheer. . . . He actually took possession of the dead man’s mouth, and he and his mate brought forth a brood of young cannibals’ . As a result of these strange circumstances, a poem was coined:

‘There were ten tongues all in one head

The tenth went out to fetch some bread

To feed the living in the dead’

During a period of high winds in early 1850, the gibbet post finally blew down. ‘Thus the last of the Lincolnshire gibbet-posts has perished, most likely greatly to the joy of the neighbouring lord of the manor’.

It was later reported that Benjamin Suttaby, saddler and Saxilby Parish Constable, had possession of the remains of the post and irons. The last remaining piece of the irons, the head-collar, can now be seen at Doddington Hall.

The Folklore

The folklore which still exists today arises from a story based on the facts of the case written by Thomas Miller and published in the Lincoln Times on 26th November 1859.

Miller was born in Gainsborough in 1807. Employed as a basket-maker in Nottingham, he was encouraged by Thomas Bailey, a Nottingham author, to print some of his poems. These inspired the patronage of Lady Blessington, who persuaded him to move to London where he became a bookseller, and continued to gain patronage for the publication of short stories and poems. Known as the ‘Basket-maker Poet’, a considerable number of poems and novels were published in leading journals from 1838 until his death in 1874.

E R Cousans, the owner and publisher of the Lincoln Times was sent two stories by Miller from his ‘Sketches of English Country Life’, for possible publication. Two letters from Miller to Cousans, together with his original handwritten manuscript for the tale ‘Drinsey-Nook and Tom Otter’ are held in the Lincolnshire Archives.

It is clear from Miller’s covering letter that the story was never meant to be more than a piece of historical fiction. He writes ‘Could you send me any little history of the neighbourhood of Lincoln that would enable me to pin a story to the tail of a fact now and then. To “lie like the truth” is the great secret in writing tales of fiction’.

All the existing tales are based on Miller’s story. The full transcript of the tale can be found at this link. The following is a resume of just one of those stories currently circulating.

‘Tom lived in the county in the early 1800s. His story begins when he met a young girl called Mary Kirkham. The two became very close and then Mary eventually gave birth to Tom Otters child. The laws of the day stated that Tom must either marry her or go to jail. Despite the fact that he was already married, on 3rd November 1805 Tom took her to be his wife.

That night while they walked home together Tom killed Mary with a hedge stake. It was not long before the murder was discovered and Tom Otter was arrested and charged. He was sentenced to death at a trial which took place at the Sun Inn, Saxilby.

Mary Kirkham's body was found in the lane and was also taken to the Sun Inn. As the body was brought in, blood spilled onto the steps of the Inn. This blood was said to have stained the steps for many years after the murder took place, no matter what attempts were made to clean them.

On 14th March 1806 Tom Otter was hanged and then the body was fastened in irons and hung upon a high post. Even this event was surrounded by tragedy - the body fell from the post twice due to the weight of the irons and upon falling the second time crushed one of the men and killed him.

The stake with which Tom Otter killed Mary was kept for many years. Every year on the night that the murder took place the stake would be removed from wherever it was being kept. Many attempts were made to secure it using iron hoops or staples, but nothing was found that could hold it. The following morning, it would be found in the spot where the murder took place and would be 'wet with gore'.

No one knew what or who was moving the stake and it was eventually burned by the Bishop of Lincoln in the yard outside the Cathedral’

An article appeared in the Lincolnshire Chronicle a week following publication of the tale - ‘A series of articles entitled Sketches of Country Life, by Thomas Miller, have recently been commenced in the columns of the Lincoln Times, and No.2 relates to Drinsey Nook, near Saxilby, and the murderer Tom Otter. The article is of such an extraordinary character, so full of manifest absurdities, and so perverse to the true fact, that it has caused more than a fair share of attention. The Saxilby people, who are well aquainted with the story, are indignant, and condemn in strong terms what they say is a mass of falsehood and superstition. Lincoln people, on the other hand, laugh at the nonsense, fully understanding how the author of the ‘sketch’ has drawn largely on his imagination for the purposes of exciting the wonderment, and pandering to the superstitious ideas of that large class of rural population who yet believe in ghosts, hobgoblins and witches’.

Ghost hunters still visit the Sun Inn, in pursuit of a tale from a Victorian author. Miller’s tale reads ‘For years after they say the cries as of a new born child were always heard in the room where the murdered woman was placed, and that was every 3rd of November.’

It is fascinating then that a piece of historical fiction from the pen of a contemporary of Charles Dickens still interests today.